On writing, editing and vodka shots

The first in a two-part email conversation between author Ramona Koval and senior editor David Winter about writing, editing and the benefits of an occasional shot of vodka.

David Winter: Hi, Ramona. Well, here we are two weeks from printing Bloodhound. We’re down to the last corrections to the proofs. Once it’s all ready, we’ll wait for another fortnight until the copies come in. Then we can toast your new book! It will only be one more month till it’s on sale! So, here are your choices from the Text bar: tap water, Mandy’s fizzy drink (don’t choose this), Marcus’s sparkling mineral water, sparkling wine, red wine, white wine, beer, HG’s Delicious Birthday Vodka Straight from the Freezer. I bet I know what you’ll choose, as your shindig for By the Book is still the only book launch I’ve been to where the author was doing shots before the speeches. More’s the pity...Anyway, can you tell me how you found your favourite poison?

Ramona Koval: You are so right, David. I’m all for HG’s Delicious Birthday Vodka Straight from the Freezer. I hope there is some left, although I need only one shot. Or at the very most, two. Then I will drink tap water for the rest of the night while I observe the bad behaviour of others. My family were not great drinkers. Perhaps a vodka or a brandy at a wedding or bar mitzvah. I heard about vodka not leaving an after-smell on the breath and I thought that was neat. I haven’t really developed a taste for wine. A shot of vodka is all I needed for courage. Whenever I have tried fancy cocktails I have regretted it in the morning. And for the rest of the week.

DW: Just a shot for courage, then watch others’ bad behaviour—I like that. I’ve always found that white spirits make me a bit crazy; but I’d not heard about vodka having magical breath properties, so maybe I should give it another try. Perhaps you could explain a bit about what you’re celebrating? I mean, beyond a new book, which is always a huge thing. The action in Bloodhound—the quest to find out who was your biological father, and all the things you do to further that quest, the wild detours and so on—takes place over about fifteen years, but in a sense it’s the story of your whole life. From a young age you believed your father was not your real father. People who know you as primarily a broadcaster might be surprised to know that for all that time you’ve also been an undercover detective of sorts, albeit in the genealogical sense. Is it hard to stop searching—can you ever really give up being a bloodhound?

RK: It was a revelation to me when I realised I was a bloodhound. I had the smell of a story in my nostrils and there was almost nothing I could do about the urge to follow every clue to resolve it. After a few years I began to realise that much of my life’s work had prepared me for the chase. I had studied science because the world was confusing to me and I found it exciting to think that there were immutable laws of science that could make the world more predictable. I studied genetics, of all things, because I was fascinated by the idea that traits could be handed down through families. I became a journalist, a professional asker of questions, to be able to follow my hunches, my interests and my gut reactions, as well as my intellect. Everything seems, in retrospect, to have been ordained by my need to know more. Can I ever give up being a bloodhound? Could I possibly have been anything else?

And what about you, David? Since we are going to talk about editor–author relations, what made you into an error hound? Or a hound sniffing out the best book a manuscript can be, hidden behind the miasma presented by the author?

DW: Well, you have to aspire to do all the detail, and also come up with creative insights that help an author to lift up their manuscript a level or two. And there’s the talent spotting, too. So it has the appeal of needing to get very different attributes working simultaneously. Why me, though, I don’t know...the percentages are better than anaesthetics: ninety-nine per cent boredom, one per cent terror. Editing doesn’t pay as well as anaesthetics, but the risk of losing someone on the operating table is so much lower.

I know you’re thinking now about what book to write next, and considering heading back to science. Science, in fact, infiltrates most of the chapters in Bloodhound. When you’re tossing ideas about, what do you consider—what do you worry most about? Is it whether a subject can sustain your interest, or whether readers will want what you have to say, or other things? (I worry about sinkholes. Maybe you could write a book about how they seem to be opening up everywhere at the moment.) On a tangent, how do you rate the health of long-form non-fiction writing at the moment, at the literary end of the spectrum, and whose writing in that area has grabbed you recently?

RK: Ah yes, sinkholes. I just watched two South Koreans get off a bus and walk a few steps and disappear beneath an innocent-looking pavement. Sinkholes are indeed intriguing. If I were to write you a book about them I would have to be transported by the idea of them, by the story of the why and the what and the how, by a range of ideas and disciplines—history, psychology, geology, game theory, human ingenuity, urban development, I could go on—and now I see I am almost talking myself into the possibility...

For me, the next big project will take me across the space–time continuum and introduce me to a range of utterly enthralling ideas. It will certainly not involve any complex negotiations with my family. I’ve found that my enthusiasms, well told and researched, will interest enough people to make the project viable. Is the idea sustainable into a book? Will it take me over? These questions are the start of things, and then I let the momentum of passion and persistence take over.I

have immersed myself in Bloodhound for the longest time, and almost to the point of singular obsession over the last year, so I have not been able to read widely in other areas, but I’m convinced of the continuing health and vitality of long-form literary non-fiction. It’s the form I love to write and to read. I find it compelling and in these revolutionary times—digital, humanoid, terrestrial—I’m compelled to understand just what’s really going on. I’m attracted to books about one thing—sand, rubber, fishing, whatever—and knowing everything there is to know about that thing.

When you say you worry about sinkholes, do you dream about them? I’m just remembering that phrase people use about wishing there was a way for the earth to open up and swallow them, getting them away fast from where they didn’t want to be...like getting sucked into a black hole. Did you see that film Interstellar? I loved it.

DW: There’s something primal about it, isn’t there: we depend literally on the ground beneath our feet, and figuratively on all the sayings about it. I’m glad to say I don’t dream of sinkholes, because that would be the same old falling nightmare most of us have as children. (My dreams are both more elaborate and more banal now.) Did you see the news this morning that scientists have discovered a black hole the size of twelve billion suns? I don’t find it any easier to process that kind of information now I’m older; I just make a quiet groaning sound, then worry about whether there’s any yoghurt left and why does there have to be an editorial meeting this morning and would the cat stop howling for no reason.

I haven’t watched Interstellar yet; I should, but I feel like I’m on a downward trajectory with Christopher Nolan. I love reading about space: Lem’s Solaris is amazing, and I dragged myself through Mailer’s A Fire on the Moon recently, which is an incredibly detailed and brilliant explanation of the science of the moon landing, but also has the author constantly referring to himself in the third person as Aquarius...Have you read it? I much prefer your approach in Bloodhound, the unabashed ‘I’, an unpretentious first-person narrator who confides in the reader instead of reaching out to punch them in the face.

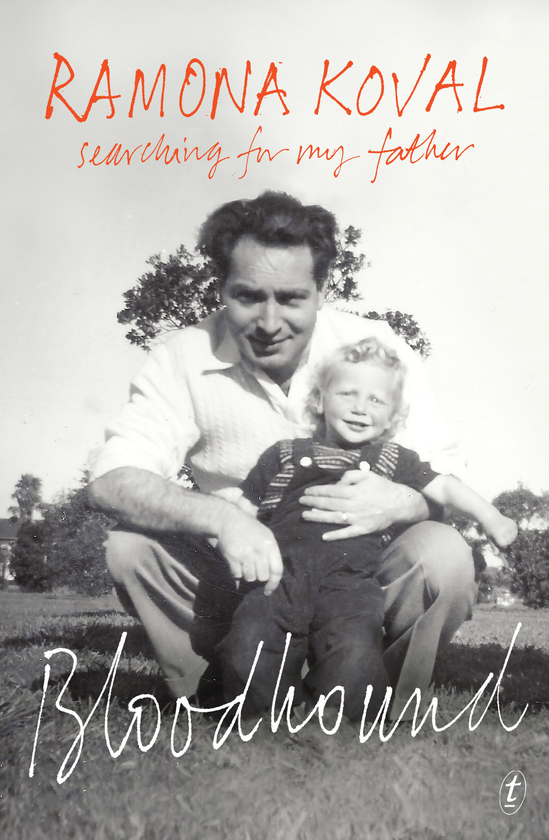

So, I’d like to get down to the nitty-gritty. Let’s talk about the past few months, gloves off. What’s been the hardest thing for you in the publishing process? For me, getting my head round the time shifts in your story—the chapters of Bloodhound switch between different periods in the past fifty years—and returning to the Holocaust stories, particularly the testimonies at the war-crimes trials, have been the biggest challenges. But I wonder what it’s like for you, not just the editing and reworking but also being presented with a cover design showing you as a child with the father who raised you, the man who you’ve always felt was not your dad. This must be confronting? Or is it no big deal after having watched countless hours of survivors’ accounts of the death camps?

RK: I must say it was a shock to see the cover design, the little toddler girl, me, leaning into the squatting haunches of Dad, in his thirties then, so much younger than I am now. We are in a park and the big tree behind him is a kind of ominous presence. I’m smiling, unaware of the path before me. He always looked uncomfortable in photos, so maybe it’s not me that’s caused it. Or maybe it is. Did he have an inkling of the tenuous link between us? It seems rather private, this photo. I never imagined it was going to be the cover of this book, the code for my story of chase and revelation. At first I thought it was too close to home, and then I remembered the whole book is close to home, close to the bone.

Bloodhound

Ramona Koval

I had some hard months of research, watching and reading Holocaust survivors’ testimonies, but I could pause the film or put the book down and get some fresh air whenever it got too hard. Which is more than they could do. So I owed it to them to persevere.It was worrisome to negotiate the path of this book through family and those to whom I was indebted for information and help. A writer wants to write. Others prefer not to broadcast their stories. I had to come to an understanding with people while protecting important relationships. I had to wait for the main protagonists to die. It took fifteen years, but that was exactly the right time for the book to cook. It couldn’t have had the twists and turns and what I hope is the mature resonances if I had spent a moment less on the task.And—thinking about your problems with time shifts—aren’t we lucky to have your facility with the English language and knowledge and skill with tenses in all their glory. When someone tells their story, they hold all the time shifts in their head, the stories melding backwards and forwards, meanings being generated, foreshadowed and skirted around. It was wonderful to have your careful eye clarifying the writing, honing the story so that meaning was sharpened.

DW: In the book you mention briefly a couple of times your years of psychoanalysis. That can be a process of story-making, to make sense of the past. Does the act of writing your story for readers, making it public, have any therapeutic value? Or does it feel like a different process? Readers will see that Bloodhound becomes more and more about stories: about why we need them.

RK: Yes, I mention some four and a half years of psychoanalysis. It was an attempt to test the story I was telling myself about the way things had been, the way they were. I embarked upon it after I returned from Poland and had made a radio documentary called The Cellar, the Hinges and the Copper Samovar. I had thought that making the trip and the doco would be liberating, but I was still feeling a bit confused about the identity of my father. I remember being very suspicious of my analyst at the beginning. I couldn’t find very much that he had written about the process. I was doing my research as usual. He told me that it was very hard to write about what might happen. How to connect various dots, dreams, misapprehensions and transactions to make a coherent story? In the end it is hard to say exactly what I was left with, other than some strands of story that I felt I knew well, that had stood the test of the telling.It was years after this time that I started writing Bloodhound. And because I was not sure where I would be taken with the unfolding quest, where I ended up was a surprise for me and, yes, a kind of relief, too. And yes, psychoanalysis is a very different experience than writing was, but both approaches were additive and mysterious.

DW: I like your phrase ‘stood the test of the telling’. Irvin Yalom had a case study in the New York Times the other week, ‘A Curious Case of Writer’s Block’. He describes the end of their one consultation, the patient saying: ‘I regret having to leave you with so many riddles...but I’m afraid our time is up.’ I loved the role reversal. Are you a fan of TV shows with analysis storylines (Dr Katz, The Sopranos, In Treatment)?

RK: I just read Yalom’s piece. It is improbably amusing, and I get the delicious reversal of the patient deciding when the doctor’s time is up. The only TV show of those that I followed closely was In Treatment, which I thought was wonderful. I especially loved the behind-the-scenes view of what was really going in the analyst’s life, and the wonderful weekly visits to his own therapist. We imagine that the analyst holds all the wisdom in his hands/head, and it’s a shadow worry to imagine that this is not the case. Can you really trust him? You can learn quite a lot from what your projections about the life of the analyst might be.After it’s all said and done, and you’ve bid your goodbyes, it can be even more fun to discover where the truth lies! These social and professional circles can be quite small really, and overlapping in a most amusing way.