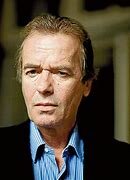

Martin Amis

Novelist, essayist, memoirist and critic Martin Amis is also professor of creative writing at the Centre for New Writing at the University of Manchester. His novel, The Pregnant Widow, is the story of the sexual revolution of the late 1960s and 1970s as experienced by narrator Keith Nearing.

He's looking back from the age of 56 at his life — particularly at the summer of 1970 when he was almost 21, a student of English literature and sharing a castle in Italy with a group of friends. Feminism was emerging in its second wave and women were trying to come to terms with new freedoms. Martin Amis is in conversation with Ramona Koval at the 2010 Cheltenham Festival of Literature.

Audio

Transcript

Ramona Koval: Was the sexual revolution a bloodless one? Did anyone get hurt? Are we still hearing its good vibrations or maybe we're still paying the price to this very day. As Martin Amis explains it to me and to the audience at the Times Cheltenham Literary Festival, this is a novel that looks at those changes and how time speeds up and slows down at different parts of our lives.

Martin Amis: Well, it does. The 50s of your life are like a bullet train, it seems to me, the years tumbling over each other like puppies playing, whereas in earlier phases of your life, particularly adolescence, which goes on into one's early 20s, all that time of yearning and erotic and romantic desperation, time is very static. And I hoped to get that, to make it a kind of suspended world, this long summer of intrigue and yearning.

Ramona Koval: And the way you've structured the novel makes the bullet train clearer because it gets faster and faster as one gets towards the end. Suddenly the years are going in short chapters and decades go quickly.

Martin Amis: Yes, and the last...this novel began life as an endless and hopeless and ridiculous autobiographical novel, and it was a completely dead thing. It had no life in it at all. And I made a couple of obvious and tardy realisations. The first thing is that it's impossible to write autobiographically about sex, it's completely disgusting, you can't do it without striking an attitude. I think that very few writers have got anywhere with sex.

My father used to say you can refer to it but you can't describe it. And you can describe fiascoes and disasters, but you cannot describe that which gives it its special status in our lives because it is after all the act that peoples the world, it's a highly significant act, and yet what we're seeing now I think in a kind of second wave of the revolution is that less and less significance is being attributed to it. Its connections with childbirth are much thinner than they used to be.

They used to say that in the 17th century the poets stopped being able to think and feel at the same time, disassociation of sensibility. And I think what's happened in the generation that came after me and again after them is the separation of emotion from sexuality, which I think is very alarming. It's a hatred of significance in sex, and let's be honest about this, that any child who can walk has probably seen hard-core pornography on the internet, that's their sexual education now, not dissecting a worm in a biology class or being told by your drunken father.

Ramona Koval: Is that what happened to you?

Martin Amis: Yes, it is.

Ramona Koval: What did he say?

Martin Amis: Actually he told us a joke, it's not a bad joke and I'll tell you it, and I told my sons the same joke, and there was a marvellous little pause and then a great shriek of laughter. In this joke Farmer Giles is being nagged by his wife to tell little Joe, their son, about the birds and the bees. She says, 'He's 12 now, he is going to be 13, you've got to tell him about the birds and the bees,' and Farmer Giles says, 'Oh it's a bit embarrassing for a bloke, I don't really like to bring it up.' She said, 'No, come on, you've got to do it before his 13th birthday.' So one afternoon he takes his son up onto the top of the hill and says, 'Your mother thinks I ought to tell you about the birds and the bees.' And Joes says, 'Yes, Dad.' And he says, 'You know what you and me did to those girls in the ditch last Friday night, well, the birds and the bees do it too.'

Ramona Koval: But this wasn't your first introduction to sex from your father, was it?

Martin Amis: No, the next day I think he told us that. He described it well, he said...and I remember, we were on our first holiday abroad and I was playing a pinball machine in a bar in Sitges in Spain and my brother came up and said, 'Quick Mart, Dad's telling us the lot.' So we already knew what 'the lot' was, but like everyone else you've probably got a rather nasty version in the schoolyard. And as Kingsley wrote, when you tell your children about it it's not because you think for a minute you're telling them something they don't know, but you're giving the sanction of parental approval and you're saying that it's official that you know.

Ramona Koval: Were you shocked by the whole thing ever?

Martin Amis: I was incredibly shocked when I was told in the schoolyard, and in fact I refused to believe it.

Ramona Koval: It is unbelievable.

Martin Amis: It is, and I said my father would never do that to my mother. But to go back to writing about sex, DH Lawrence, he is the pivotal figure in this book because my character has just changed subjects to English literature and he has to read the entire English novel during this long summer. And it is amazing, and I did sort of re-read the English novel, that the subject was always, from Clarissa on, that's 1650 or whatever it was, it's all about whether women are going to fall, and they can only fall if they're drugged at first. This goes on being true for a century and a half. Richardson is in a great lather all the time about violation, but of course a heroine can't do that unless she is not herself. So the villain always drugs the heroine. In Fielding, which is a much more relaxed world, you're allowed to have sex if you are a farm girl or a decadent society hostess. But Sophia Western, the heroine, certainly not.

It goes on being this way right through to Jane Austen, and it is true that Jane Austen, none of the heroines fall, but in every book someone falls. In Pride and Prejudice it is Lydia, the little sister of Elizabeth, and in Mansfield Park it's the two Bertram girls, both of them, it's an incredibly traumatic event. In Northanger Abbey it's Isabella Thorpe, and her life is over. Same in George Eliot, you know, with Maggie Tulliver with Stephen Guest, Mill on the Floss, and they're on the River Floss in the punt, and she begins to lose her self-possession and something happens, and that's Maggie's life gone. Right through to Hardy. And then along comes Lawrence, and suddenly it's no great matter whether women fall, it's just part of adult life. But I don't think he had any success in describing the actual act. And John Updike, who spent a lot of time describing the sexual act...in fact he sends a little Japanese film crew into the bedroom and describes it in embarrassing detail...

Ramona Koval: What about Henry Miller and the Americans? Did they have a go at it? Did they succeed?

Martin Amis: Henry Miller is the sort of fringe, isn't he...

Ramona Koval: I think we used to pass around Henry Miller books in my school...

Martin Amis: With all the bits marked and everything.

Ramona Koval: Well, you didn't even have to mark them, it fell open at that page. That seemed pretty hot.

Martin Amis: Yes, but Henry Miller is sort of second rank and not...well, there's been plenty of catchpenny novelettish stuff.

Ramona Koval: So you're talking about art and writing about sex.

Martin Amis: Yes, writing...there are all sorts of terrible ways to do it in the genre type fiction, like the English version where they say, 'Towards morning I took her again,' you know. The pulpy stuff that was so beautifully parodied by Kurt Vonnegut which is, 'She gave out a cry, half pain, half pleasure (how do you figure a woman?), as I rammed the old avenger home.'

Ramona Koval: But you said you were writing autobiographically about sex, but doesn't every writer writing about sex...aren't they letting us into his brain? It has to come through your experience of it. We really know it's your experience.

Martin Amis: That's the trouble with it, writing about sex, because the novelist, unlike the poet, has to be a universal figure, he has to be like an everyman, and a poet is an individual or nothing. And a poet can suggest things that a novelist has to spell out. But the trouble is that with our sexual urges, they are immediately universalising. The polymorphous perverse, as Freud called it, in your case will have many quirks that aren't shared by everyone else, whereas the whole business of writing a novel is this gamble that your feelings about certain events in life, about youth and adolescence and love and divorce and having children and losing a parent, that your feelings about this will be representative. But you can't say that about sex.

Ramona Koval: Why do you say that the novelist has to be everyman and the poet has to be singular?

Martin Amis: There's a brilliant sonnet by Auden called The Novelist. And the first eight lines are about poets, with lots of lines like, 'They can dash forward like hussars', they live so long alone they're these sort of eccentric, slightly mad figures. And he says that the novelist isn't like that, the novelist must make himself 'the whole of boredom', 'among the just be just, among the filthy, filthy too'. And that's exactly right I think, that you have to open yourself up to experiences in a way that is almost passive compared to the poet who takes the world by the scruff of the neck. Novelists can't do that, they have to watch and empathise.

[The Pregnant Widow, reading from When he was young... to ...this is the past.]

Then we go back to book one where we lay our scene, 1970, and the famous lines from Philip Larkin:

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me)&$8212;

Between the end of the Chatterley ban

And the Beatles' first LP.

I think he got the year wrong actually, I think sexual intercourse began in 1966 but was certainly well advanced by 1970.

Ramona Koval: Why do you say 1966?

Martin Amis: Do you think this is a mad theory? The First World War ended in 1918, and then there was a 21-year gap, and you got the Second World War. So 21 years after 1945 is 1966, and at that moment, and I can remember it almost, everyone realised that they were going to break a tradition that had established itself over two generations which was to send the youth of Europe out to kill each other. This had happened twice, for your parents and your grandparents, and suddenly everyone realised this wasn't going to happen. And this was the moment that the status of youth really climbed because my parents' parents couldn't love them with the abandon that my parents loved me because everyone knew that fascism meant war and the whole of the '30s was just a question of when was this massacre, this great slaughter going to happen again. And it clearly wasn't going to happen again in 1966 but...

Ramona Koval: Well, it depends where you were because Vietnam was...

Martin Amis: I'm talking about Europe.

Ramona Koval: Well, the world is bigger than Europe. If you're going to make a general...

Martin Amis: But all the slaughtering took place in Europe, and that's...

Ramona Koval: But I meant the coming war, there was Vietnam coming in another part of the world.

Martin Amis: Vietnam was there, and there was the Cold War which was the strangest kind of war, it's been well described as the contest of nightmares and you only fought in it in your dreams and in your subconscious, and the rest of the time you just pushed it to the back of your mind. But anyway, the sexual revolution did occur.

And I'll just close by reading the three epigraphs at the beginning of the novel, which are usually put in there by the author to show how incredibly well-read he is, and often there are extracts from Russian art criticism that is only available in Italian or something. But mine are not obscure. I'll read the first, it's from Alexander Herzen, the 19th-century Russian thinker, which explains the title, The Pregnant Widow:

'The death of the contemporary forms of social order ought to gladden rather than trouble the soul.' He means social as well as political revolutions. 'Yet what is frightening is that what the departing world leaves behind it is not an heir, an inheritor, but a pregnant widow. Between the death of the one and the birth of the other, much water will flow by, a long night of chaos and desolation will pass.'

The second quote is from the Concise Oxford Dictionary:

'Narcissism: noun: Excessive or erotic interest in oneself and one's physical appearance.'

And the last quote is for a book I can't recommend highly enough, Metamorphoses, Ted Hughes' Tales from Ovid, which opens with the lines:

'Now I am ready to tell how bodies are changed

Into different bodies.'

Throughout the novel I tell the story of Echo and Narcissus which I think is not only tremendously beautiful but tremendously resonant for this story. Echo is a beautiful nymph who has been cursed by Juno so that she can only repeat the last thing she heard. She falls in love with a rather cruel-looking glassy youth called Narcissus and can't address him anyway because she can only speak when she's addressed.

She watches him from afar, and then one day Narcissus is out hunting with his friends and he becomes separated from them and he shouts out, 'Where are you?', and Echo of course shouts back, 'Where are you?' And he says, 'I'll come to you, ' and she says, 'I'll come to you.' And they talk at cross purposes for a bit, and then he says, 'I'll meet you halfway,' and she says, 'I'll meet you halfway.'

And they come to a clearing and Echo, who is very beautiful, edges out into the opening and Narcissus says, 'Never, I would rather die than let you touch me,' and he walks off, and she sinks to her knees, and what does she say of course but, 'Touch me, touch me, touch me.' Echo then dies of a broken heart, and a male admirer of Narcissus who also had his heart broken raises his voice to Heaven and says, 'Let him suffer, let him know what it is to love and have nothing come back.' And the lovely lines, 'Nemesis, the corrector, heard this prayer and answered it.'

Now, Narcissus is out in the countryside, he comes to a beautiful small pool that has never been slobbered in by animals or skated on by insects, and he looks down and he sees a beautiful face staring up at him. He collapses like a fallen garden statue and stares into the pool. But he goes on gazing and he says to his reflection, 'What is it? I tell you I love you, you seem to say you love me, I reach down to kiss you and you seem to reach up to kiss me, but then you scatter on the water.' Then he realises that it's him he loves, and that this is by definition something he can never fulfil. And he dies in a day and a half, and the ghost of Echo, or Echo's echo echoes his last words, 'Farewell, alas, alas.'

And then when he enters the land of the dead he can't resist and runs straight to the River Styx and looks down, but all he can see is the smear of his shadow on the troubled waters.

And it strikes me that what we've all had to do is fall out of love with our own reflections. Whereas it takes Narcissus a day and a half to die, it takes us half a century to fall from our prime. Narcissus never had to love himself when he was old and wouldn't have done, and that is our journey.

Ramona Koval: Do you think it's impossible to love oneself when one's old?

Martin Amis: In that kind of narcissistic way, yes, excessive or erotic interest in one's own body, I think that goes. I also said to my wife once, I said, luckily beyond a certain age the mirror doesn't actually tell you what you look like. It's rather like the shadow smear that Narcissus sees in the River Styx.

Ramona Koval: Is this because you're not wearing your reading glasses when you're looking at it?

Martin Amis: Well, you're certainly not wearing your reading glasses...

Ramona Koval: Because it's got a nice blur, doesn't it.

Martin Amis: It's not a blurry enough, and absolutely horrific when you put your reading glasses on. But it's not really narcissism, its death that one's face...there's a Saul Bellow novel where he sees in his 30-year-old girlfriend the first lines thickening under the eye, and he says, 'Death, the artist, very slow.' And it is very slow. But that horror film I mentioned, it does become a sort of snuff movie, and long before that you are its trailer, you're an ad for death. Death is the opposite of Eros, this is our human tragedy.

Ramona Koval: But not all of Martin Amis's novel is about age and regret. His protagonist in The Pregnant Widow, Keith Nearing, is looking back to the '70s when young people were discovering all manner of new freedoms. As Martin Amis sees it, the sexual revolution was a particularly difficult time for women, and he draws on personal and family experiences for his three main female characters, trying to find their own way in the new era.

Martin Amis: One of them tries to join the freer spirit and is just pulled back by something at the very last minute and can't go through with it, and it's to do with religion, it's to do with that thing about saving yourself and your husband and not having sex without love, those layers of ideology that you hardly know you have in you, but they are all there. So there were people who dipped a toe in it or not even, and then retreated.

There were people like the character Lily, and I think this is the vast majority...and all the clever ones did this, where they felt their way into it. And it was very difficult because when girls looked about...how are we going to behave with this new freedom? And they looked at the boys and thought, well, we'll be like boys, because that was the only model. And then very quickly I think in a few years every girl realised that behaving like a boy was not in her interests. So they perhaps went a bit too far at first and then found a modus operandi that they could live with and enjoyed the freedoms and learnt the new rules and the new advantages.

All the difficult choices, by the way, fell to women. The boys just went on being boys, only more so. And then there was the kind of girl, I think a minority, but who went far too far in the other direction and behaved more like boys than boys did. I'm afraid my sister was an example of that and she is...well, she's been dead for over ten years, she died at the age of 46, I've written about her quite straight in here, she is the younger sister of the main character. The freedom was just too much from her and she got it all wrong, and sort of used herself up and died at the age of 46.

Ramona Koval: Was that about using sex to trade for love or to trade for attention?

Martin Amis: Just because it was the thing you could give, and she had a great heart actually, but she didn't realise that you're not an infinite supply of yourself, you have to husband yourself, you have to keep some sort of containing action on the self, and she's sort of dissipated herself, and I think then drank a suicidal amount just because of all these confusions.

Ramona Koval: You are the father of daughters. Tell me about how you think about their growing up and sexuality and what you tell them.

Martin Amis: I'm not going to tell them the Farmer Giles joke.

Ramona Koval: I think they're just about at the age where you should have already had this talk maybe.

Martin Amis: My wife has had it with them.

Ramona Koval: This is pretty amazing, don't you think?

Martin Amis: No, I think that's how it's always been, hasn't it...

Ramona Koval: But you've learned such a lot about women and sexuality and freedom and love, why not convey it to them?

Martin Amis: Because there's a physical change that comes over girls that has no equivalent with boys, and they don't want to talk to me about that, that's not the father's place to be...

Ramona Koval: No, but I wasn't talking about the biology of it, I was talking about those things that you just said, about husbanding oneself, as you said, or is that about saving part of oneself? You're not going to tell me you're going to tell them to save themselves for their husbands, are you?

Martin Amis: No, what I do tell them and have been telling them for a while, they're 13 and 11 now, is a sort of rule for life that applies to this if you care to apply it, and it began when I was just saying, you know, don't get kidnapped, I said, 'Don't let anyone make you do something that you're not 100% easy about.'

And I've told them this too; one of the cousins that I used to go and visit in the village of Gretton was eventually murdered by Fred West in Gloucester. And she was very studious, brilliant and religious girl of 21 or 22, very sensible. Now, he got her into that car by the following means; he had his wife sitting next to him and she had a baby on her lap, and he said, 'We'll run you to your village,' she was waiting for the last bus. And I say to my daughters, no, and if you have any unease about anything don't be coerced about anything. So don't let your peer group coerce you, don't let the current ideas of what's smart and hip coerce you, be yourself. And I think what else can you say.

Ramona Koval: I think that learning to listen to yourself is something that sometimes takes you 50 years or 60 years. That is a very important thing that you're telling them.

Martin Amis: It is. But true, don't you think?

Ramona Koval: Absolutely.

Martin Amis: Because I think we are swayed by half-digested inherited formulations that are kind of like clichés of the mind. You think you're independent and your own agent and all that, but in fact your head is full of these things that are just acculturated within you.

Ramona Koval: The pregnant widow, the long gestation of the new time, the new social order, how long do you think it will take from the start, from '66 say...or do you think it's going in that direction still or is it moving back? What's happening?

Martin Amis: No, it's not going to move back. The only thing that could move anything back would be an enormous war or a huge crash, much bigger than the one we're living through now, otherwise it will just continue forward. But I think the pregnancy of feminism is still in its first trimester. And I've become more and more millenarian feminist the more I thought about this, and I think that it's very much in men's interest for women to rise in society. Look at the male record, it's not tremendously impressive, is it. There have been I think 21 or 22 women heads of state, and I see you've got a Sheila running things down in...

Ramona Koval: We've got a Sheila now, by the skin of her teeth.

Martin Amis: And we soon will have one, everyone thinks, in Brazil. Of these perhaps eight or nine of these heads of state got the job through inheritance or marriage, but nonetheless Golda Meir, Margaret Thatcher, nearly Hilary Clinton...but the trouble with female rulers, it's now constituted, is that a woman can't get to that position without giving the impression and certainly saying that she's as tough as any man. What we need is for women to come into positions of power while retaining their female qualities.

Science tells us that there are only very tiny differences between men and women in their physiology and psychology, they're marginal, negligible. But we all know that not just centuries but millions of years of acculturation, of patriarchy, going right back to our separation from the apes...it's not just a reaction against Victorianism, it's against a five-million-year-old violent patriarchy. Acculturation, as we all know in our souls, makes women more sympathetic, more empathetic, kinder, less prone to violence, et cetera, we all know these things. So I think our salvation lies with promoting these female qualities.

Ramona Koval: There you have it, English writer Martin Amis, son of Kingsley, at the Cheltenham Literary Festival, with his ideas on women, feminism and ageing. His latest book is The Pregnant Widow and it's published by Jonathan Cape.

Publications

Title: The Pregnant Widow

Author: Martin Amis

Publisher: Vintage